Nicholas Kristof, NYT, invites university students to apply for his 2020 win-a-trip contest. He has been holding these contests since 2006, and takes the winner along with him on a reporting trip to cover global poverty, health and social justice issues. Read more.

Call for Papers: Decentering ethics: Challenging privileges, building solidarities. University of Ottawa, Ontario (Canada).

Local organizers: Sophie Bourgault (University of Ottawa) and Fiona Robinson (Carleton University)

Care ethics first emerged as an attempt to ‘decenter’ ethics; feminist philosophers like Carol Gilligan argued that women’s moral experiences were not reflected in the dominant, masculinist approaches to ethics, which were centered on a rational, disembodied, atomistic moral subject, able to self-legislate or engage in moral calculus to determine principles of right action. Care ethics challenged this model by positing ethics as relational, contextualized, embodied and realized through practices, rather than principles. Over the past decades, many care ethics scholars have sought to further this project by considering care politically, in relation to the various intersecting hierarchies of power and privilege that inhere in the context of modernity. At this time of political and ecological crisis, there is an even more urgent demand to reflect on this project of decentering ethics and to ask what further work there is to be done. To what extent has care ethics been (un)successful in decentering ethics, challenging privilege and building solidarities? How can ethics – and care ethics in particular – address questions of race, indigeneity, class and gender? How can a care ethics approach help us to reflect on the question of privilege – of moral subjects and of moral/political theorists – while also creating spaces to build solidarities?

Scholars from all disciplines are invited to submit an abstract (between 250-300 words) for a 20-minute presentation (firm time limit) on the theme of Decentering Ethics. We are seeking presentations that explore how an ethic of care has addressed or can address the issues of privilege, hierarchy and solidarity in the contemporary context. All scholarly approaches are welcome including those that address or employ theory, empirical data, applications, policy, aesthetics, etc. Please note that the organizing committee encourages presentations that are not read.

Abstract submission

Please send your abstract for peer review to abstractsCERC2020@gmail.com by Friday January 31st, 2020. In the subject line, please type ‘CERC proposal’ and your last name. Individuals may only submit one proposal. In your email, please include a brief biographical note (250 words max) with main research interests and institutional affiliation (if applicable).

Attach a Word document to the e-mail that is anonymous and ready for peer review. The Word document should contain:

- the title of the presentation

- the abstract (250-300 words max), which should outline the main arguments of the paper, as well as its theoretical and/or empirical contribution(s) to the existing literature (and a few words on methodology, if applicable)

- presentation equipment requirements (if applicable)

Criteria for selection include: effective and explicit engagement with the conference theme; clarity of the abstract; contribution to the diversity of presentations, and potential significance for advancement of the field of care ethics. Panel proposals will also be considered (please include a brief description of the panel, the abstracts of three papers, as well as the name of a chair and discussant). Poster presentations may also be proposed to the organizing committee of the conference.

Decisions on the abstracts will be communicated before March 1st, 2020. Please note that the abstracts selected for our conference will be posted (as received) on our website prior to the conference.

All conference presenters will need to register for the event prior to the conference program’s official release date. Detailed information concerning accommodation in Ottawa and registration costs will be offered on the CERC website in the late spring of 2020. For questions about the conference or abstract submissions, please write to abstractsCERC2020@gmail.com.

CERC 2020 organizing & scientific committees: Sophie Bourgault, Monique Lanoix, Stéphanie Mayer, Inge van Nistelrooij, Fiona Robinson, Joan Tronto, Merel Visse

Narrative Medicine Rounds at Columbia: “Writing a Biography: The Promise and Peril of Telling Someone Else’s Life,” a talk by professor Maura Spiegel

https://www.narrativemedicine.org/event/dec-narrative-medicine-rounds-maura-spiegel/

First conference on Research Integrity Practice

http://www.enrio.eu/congress2020/

This first European congress on research integrity practices addresses current challenges that open science and data protection laws pose for research integrity in Europe.

The Hidden World of Care: MH Symposium, 11/2/19

Together with professor Joan Tronto, on November 2nd, graduate students, prospective students, faculty, and others attended the Medical Humanities Symposium to discuss “The Hidden World of Care”.

Together with professor Joan Tronto, on November 2nd, graduate students, prospective students, faculty, and others attended the Medical Humanities Symposium to discuss “The Hidden World of Care”.

At a moment of political discord in our country, it is no secret that we face a care deficit. To adequately care for our children, older people, and for ourselves has become a challenge. Care impacts us all, no matter where we live or where we were born. Although political life and institutions should help us to care better, many caregivers see organizations as hindrances to care. ‘Care’ is also narrowed to care work and a commodity, professor Joan Tronto argued, rather than seeing the full practice of care. Care holds our lives together, but it is still hidden from public space and that needs to change. During this afternoon, we grappled with questions such as: what would it mean if we would rethink our private and public commitments from the perspective of care? How should care be distributed, or who should care, for whom and why? How can we tell which institutions provide good care? And what would a caring institution look like?

Watch professor’ Tronto’s lecture here.

Call for abstracts Digital Health Care

Workshop Data and Stories in Digital Health Care. Mixed Methods for Medical Humanities

The workshop “Data and Stories in Digital Healthcare” examines the mutual entanglements of the humanities with medicine and data science. It focuses on the variety of forms in which information about health and illness travel between different stakeholders, such as patients and health care professionals.

Call for abstracts

We invite contributions that explore the following – or related – issues:

- the problem of scale in data and stories (big data, singular stories)

- data and stories as chronotopes

- reading images: data visualization, coding and aesthetics

- medical documentation and the coding of data and stories

- seriality and casuistic approaches to data and stories

- negotiating uncertainty and ambiguity through practices of quantification

We particularly invite early career researchers (postdocs, PhD-students, Master students) from the humanities, data sciences and medicine who are working at the intersections of stories and data and have a pronounced research interest in mixed methods.

Please send an abstract of max. 300 words of your proposed presentation along with your contact details and a short academic bio to: susanne.michl@charite.de and wohlmann@uni-mainz.de by October 1, 2019. Applicants will be notified by October 15, 2019.

The workshop is funded by the Volkswagen Stiftung (program: “Mixed Methods in the Humanities”). Travel expenses, accommodation and meals will be reimbursed for invited participants. A number of pre-selected speakers have confirmed their participation in the workshop; among them are Kirsten Ostherr, Fritz Breithaupt, and Arthur Frank.

Liz Newnham

Interview with Elizabeth Newnham, lecturer in Midwifery at Griffith University, Australia.

1. Where are you working at this moment?

Since January this year, I have been working as a lecturer in midwifery at Griffith University. I currently teach in the Masters in Primary Maternity Care – a postgraduate programme that implements the ‘Framework for Quality Maternal and Newborn Care’ from the Lancet series on midwifery and supports the development of maternity care leaders who can design, implement, and evaluate leading-edge primary maternity care models. Before this I was at Trinity College Dublin for two years, which was also a wonderful experience.

2. Can you tell us about your research and its relation to care ethics?

I am only at the beginning of my exploration into care ethics. During my doctoral research, which was an ethnographic study of epidural analgesia use within a hospital labour ward setting, I really started to think deeply about the idea of informed consent, an idea which is completely embedded into health care practice and based on the bioethical principle of autonomy.

What I saw in practice, in my research, and around the world within the maternity context, is that when we follow the principle of autonomy to its endpoint – when women are wanting to make decisions about their bodies, but outside of medical recommendations, then they appear neither to have autonomy nor the opportunity to give informed consent.

There are cases all over the world of women being bullied, coerced, threatened or forced into decisions about their bodies that they disagree with—this is not only unethical, it is dehumanised care. This is something I now want to explore further using a care ethical framework.

3. How did you get involved in care ethics?

As I was thinking about this problem, I came across an article by Jennifer MacLellan(( MacLellan J. 2014. Claiming an ethic of care for midwifery. Nurs Ethics, 21(7), 803–811. DOI: 10.1177/ 0969733014534878)) proposing that midwifery look to care ethics as a solution to some of these issues. This interested me, so I then read Joan Tronto’s Moral Boundaries((Tronto J. 1993. Moral boundaries: a political argument for an ethic of care. London: Routledge)) and also looked at Carol Gilligan’s In a different voice and started to explore articles on the topic. However, I was particularly drawn to the way that Tronto brought the political into care ethics.

4. How would you describe care ethics?

As a midwife who also has degree in Politics, I see care ethics as a politicised ethics. Drawing on Tronto’s care ethics argument, it is important that power relationships are made visible when we are talking about care, ethics and all things in between, such as bodily autonomy and decision-making.

There is also an emphasis on relationality—attentiveness arises between people, rather than passed from one person to another as are autonomy and consent—and on the recognition of the asymmetry of these relationships. People are not necessarily equal, especially at the time of care-giving and care-receiving, as to require care is to have some level of vulnerability.

The way that Tronto makes care central to human life is also a great shift in how we think about care. Which has traditionally been relegated to the private/female sphere, and has often been unpaid, unrecognised and undervalued, while generating wealth, goods or power has typically been hyper-valued. This is one of the most important aspects of care ethics – that care is actually central to who we are as a species and to our survival and therefore deserves attention.

5. What is the most important thing you learned from care ethics?

I am still at the early stages of learning, but I suppose at this moment the most important thing has been that the concept of autonomy, so central (and for the most part unquestioned) to my teachings in midwifery, can be unpacked to reveal assumptions about individualism, agency and equality that are not apparently obvious, and which actually recreate power relationships.

6. Whom would you consider to be your most important teacher(s) and collaborators?

I am lucky to have found several brilliant and supportive teachers/mentors over the years. But, specific to ethics, I must mention Mavis Kirkham, with whom I co-authored a recent article on care ethics(( Newnham, E., & Kirkham, M. (2019). Beyond autonomy: Care ethics for midwifery and the humanization of birth. Nursing Ethics. DOI: 10.1177/0969733018819119)).

I remember reading her work as a midwifery student – the results of an ethnographic study that demonstrated how the institution could effectively come between the midwife-mother relationship. And that really struck me. It provided an explanation, and perhaps a solution, to the discord that I was feeling in practice. It is, of course, an ethical dilemma – to be in a profession that is at its foundation woman-centred and yet midwives find themselves everyday having to support the needs of the institution over the needs of the woman.

I am also enjoying some correspondence with Inge van Nistelrooij, and some of her colleagues at the University of Humanistic Studies, Utrecht. They have extensive experience and publications in the field of care ethics, and with whom I share a common interest of care ethics in maternity. We have begun some interesting discussions and hope to work on some projects together in the future.

I look forward to collaborating with my new colleagues in the midwifery team at Griffith University. If we consider the university (and academia) as an institution with its own power relationships, Midwifery@Griffith embodies a kind of ‘care ethics’ in the practice of a collaborative collegiality that is also founded on relationality and mutual support, is student-centred, with a transformative education philosophy and commitment to improving maternity care systems in Australia.

7. What publications do you consider the most important with regard to care ethics?

Again, I am quite new to this, but I really favour Tronto’s thesis in Moral Boundaries. I have read some of Elisabeth Conradi’s work on attentiveness within institutions and the simplicity yet importance of this in practice also strikes a chord. I look forward to exploring more publications on care ethics, both seminal and emerging.

8. Which of your own books/articles/projects should we learn from?

The most obvious would be Mavis Kirkham and my recent article on the topic of care ethics in midwifery:

- Newnham E & Kirkham M. 2019. Beyond autonomy: Care ethics for midwifery and the humanization of birth, Nursing Ethics. DOI: 10.1177/0969733018819119

My PhD Thesis was published as a book in 2018 by Palgrave Macmillan and is called Towards the humanisation of birth: A study of epidural analgesia and hospital birth culture. Although not about care ethics, ethical practice and informed consent do come into it. It might also be of interest to anyone looking into hospital birth culture, midwifery practice, the experience of childbirth, maternity policy or ethnography.

Articles published from this doctoral research include:

- Newnham, E, McKellar, L & Pincombe, J 2017. It’s your body, but…’ Mixed messages in childbirth education: findings from a hospital ethnography, Midwifery 55: 53–59.

- Newnham, E, McKellar, L & Pincombe, J 2017. Paradox of the institution: findings from a hospital labour ward ethnography, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 17(1): 2-11.

- Newnham E, McKellar L, Pincombe J 2016. Critical Medical Anthropology in Midwifery Research: A Framework for Ethnographic Analysis, Global Qualitative Nursing Research 3: 1–6. DOI: 10.1177/2333393616675029.

- Newnham E, McKellar L & Pincombe, J 2015. Documenting risk: A comparison of policy and information pamphlets for using epidural or water in labour, Women & Birth 28(3): 221-227.

- Newnham E, Pincombe J & McKellar L 2013. Access or egress? Questioning the “ethics” of ethics review for an ethnographic doctoral research study in a childbirth setting, International Journal of Doctoral Studies 8: 121 – 136.

9. What are important issues for care ethics in the future?

I think care ethics, by Tronto’s definition, as ‘a species activity that includes everything we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible.’ (Tronto 1993, p. 103) is actually crucial to our future survival. The emphasis on care as a practice is a message that could help with numerous current global problems, the most obvious being the environment.

10. How may care ethics contribute to society as a whole, do you think?

Care ethics provides an ethical grounding for promoting social justice. It does this by inserting an understanding and recognition of power into ethical thinking, by placing increased value on relationality, by recognising vulnerability and embodiment as central principles of existence, by emphasising the need for a dialectical ethics that moves between practice and theory, and in doing all of this, exposing the falsehood that late capitalism and neoliberalism perpetuate – that the pursuit of profit and power, status or material possessions are to be valued over humanity, care and equity.

11. Do you know of any research-based projects in local communities, institutions or on national levels, where ‘care’ is central?

I think care is talked about a lot, especially in the health sector – but is not always understood in the same way by different groups. I know of no current Australian research in which care is central – but as I hope to begin work in this area I am sure I will find out if/where these may be.

12. The aim of the consortium is to further develop care ethics internationally by creating connections between people who are involved in this interdisciplinary field, both in scientific and societal realms. Do you have any recommendations for us?

No recommendations as such. I think this consortium is a really good starting point, because connection, especially between disciplines, is needed to keep ideas growing and developing. The CERC conference would be great way to create connections and new networks, and I look forward to attending one. There is something about having dedicated time and space to discuss concepts, current research and new ideas with other interested people – an embodied relationality perhaps – that can be deeply inspiring.

Care Ethics and Poetry

Care Ethics and Poetry is the first book length work to address the relationship between poetry and feminist care ethics.

The authors argue that morality, and more specifically, moral progress, is a product of inquiry, imagination, and confronting new experiences. Engaging poetry, therefore, can contribute to the habits necessary for a robust moral life—specifically, caring.

Each chapter offers poems that can provoke considerations of moral relations without explicitly moralizing. Topics include Poetry and Ethics, Habits of Caring Knowledge, Habits of Imagination, Habits of Encountering Singularity, and Moral Progress. The book contributes to valorizing poetry and aesthetic experience as much as it does to reassessing how we think about care ethics.

Primarily a book of philosophy rather than literary analysis, Care Ethics and Poetry includes dozens of poems. For those who view care theory as more than a normative ethic of adjudication, this will be an important work.

Care Ethics and Poetry by Maurice Hamington and Ce Rosenow.

ISBN-10: 303017977X ISBN-13: 978-3030179779

Reviews

“A lovely tribute to both poetry and care ethics and how, together, they increase moral sensitivity and joy in our relationships.”

Nel Noddings, Lee Jacks Professor of Child Education, Emerita, Stanford University

“Finally, a book that does justice to care by welcoming complexity, context and creativity. This polyvocal book delightfully and meticulously tells us the story about a performative and aesthetic approach to caring and moral progress. Slowly but surely, one becomes part of an intimate tapestry of voices of poets, ethicists and moral philosophers. Hamington and Rosenow not only provide us with new ethical language, they also evoke wonder and a longing for more.”

Merel Visse, Associate Professor of Care Ethics, University of Humanistic Studies, The Netherlands

Elena Cologni

Elena Cologni is an artist whose research practice has had a sustained in(ter)disciplinary approach. After a BA in Fine Art from Accademia di Belle Arti Brera in Milan, and a MA in Sculpture from Bretton Hall College, Leeds University, Cologni was awarded a scholarship for a PhD in Fine Art and Philosophy from University of the Arts, Central Saint Martins College, London, 2004 (CSM).

Where are you working at the moment?

I am based in Cambridge (UK), where I had also managed for a few years the artistic research production platform Rockfluid to work internationally, and address with an in(ter)disciplinary approach issues of memory, perception and place.

I am now bringing to conclusion the project CARE: from periphery to centre commissioned for the 250th Anniversary of Homerton College, at the University of Cambridge. This included an exhibition and site-specific installation developed in response to the history of the college, through research in the archive, and in consultation with the 250 Archive Working Group, including archivist Svetlana Paterson, historian of science Dr Melanie Keene, and educationalist and social historian Dr Peter Cunningham.

Can you tell us about your research and its relation to care ethics?

The mentioned project, draws on the College architecture (Ibberson Building, 1914), and on two key figures in its history: Maud Cloudesley Brereton (formerly Maud Horobin, lecturer and Acting Principal, 1903), and Leah Manning (student 1906-08). Both of international importance, they were concerned with health, well-being, and education, and I am specifically interested in how they engaged with care in domestic (Brereton published the book ‘The Mothers’ Companion, 1909) and international political contexts (Manning organised children’s escape from the Spanish fascist regime, 1929).

A display of items from the archive gives a snapshot of early 20th-century life in a women’s College, while focusing on practices of care in society and in students’ learning, through domestic studies, teachers training in medicine, health, and physical education, academic subjects which were considered less central than others, but more ‘appropriate’ for female students.

These themes underpin my sculptural installation designed in response to the 1914 Ibberson building (a former gymnasium), and echoed in the Queen’s Wing (housing the new gym) opening to a glass veranda, flowerbeds and lawn.

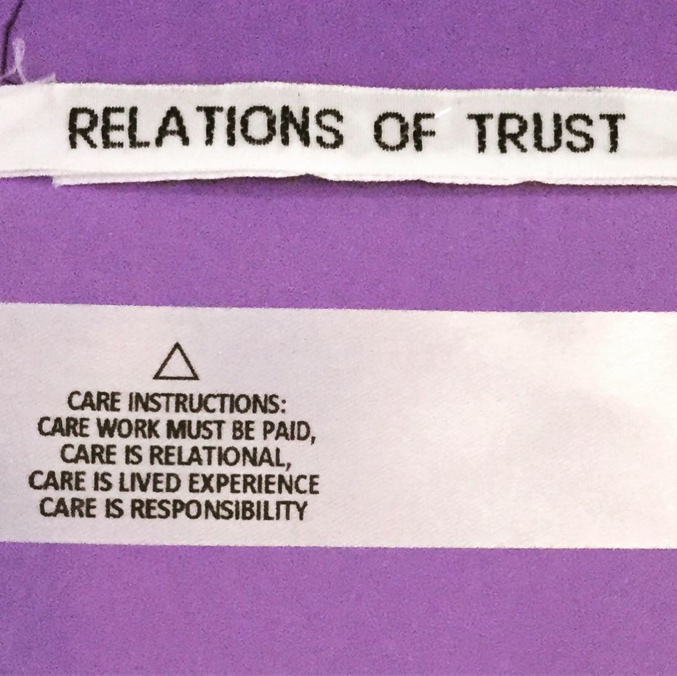

Moreover, after an exchange with care ethics’ philosopher Virginia Held, I was able to contextualise my practical work, and focus on aspects of womanhood, relationally and reciprocity at the core of the approach. This process is evidenced throughout the exhibition, including the recorded development of my thinking in a Moleskine sketchbook, and a selection of extracts from one of the publications Held shared with me informed a series of custom-made fabric labels, the steel frieze construction (Care As Support), and the steel and rope made sculptures (Relations Of Care).

How did you get involved in care ethics?

In the current project care ethics functions as the lens through which I responded to the College archive, but I have been working in this direction even if I did not addressing it directly for some time. It naturally evolved from understanding the dialogic approach in my artistic process as a reciprocal form of caring (from the part of myself as the artist, and that of the participant), while building on educationalist, sociologist and poet Danilo Dolci, who theorised and adopted Reciprocal Maieutics (1973).

Learning about his work and talking to people who were close to him, allowed me to become aware of the impact of the reciprocal giving process involved (Cologni 2016), also typical in ecological and feminist approaches. This experience still is at the core of my creative thinking and it was embedded at the time in a series of dialogic sculptures for hands (Lo Scarto).

More recently the project Seeds of Attachment (2016/18), a specific feminist lens (discussed at New Hall Art Collection in Cambridge and Freud Museum in London), allowed me to focus on undervalued roles of care in society, as I worked with region based participants, and in particular on motherhood in collaboration with the Centre for family Research in Cambridge. This had been previously addressed through the project ‘U Verruzze’ (2013), looking at trust between mother and child and curated by Vessel.

However, in the latest work, the emphasis is on the caring role of motherhood in society in a wider sense. This, similarly to other practices of care in society, is undervalued, even if hugely contributing to our economies and welfare. The project tried to identify intersections between the theory of attachment of parent and child and place attachment, by proposing encounters on the school-run (the route from home to school), thus highlighting a sort of geography of difference of caring. This was done by using a dialogic sculpture to create a physical and conceptual new place for the encounter to happen: the intraplace.

“Learning to take care also means to foster and create new connections to solve problems in society.”

ELENA cOLOGNIHow would you describe care ethics?

Care ethics allows us to step out of the dominant social, political and cultural system of understanding society and relations, and look at the peripheral (not the central) instead: the circular (not the linear) thinking, the quiet (not the loud) voices in society as strengths (not weaknesses). Care Ethics teaches and trains us not to get tempted to compete by adopting the same strategies, which have damaged our society and environment, but try different avenues instead.

Learning to take care also means to foster and create new connections to solve problems in society, something at the core of some non-western countries’ ethos (eg. Ubuntu). Essentially care ethics has listening at its core, as much as most dialogic approaches including Dolci’s, and a lot can come from practicing it.

What is the most important thing you learned from care ethics?

As an artist and academic, I have referred to phenomenology the most since early on (1999-2004), while also understanding the participants’ and audience’s reception of my work through aspects of psychology, and considering lived experience as central to my work. Care ethics showed me how to position my subjectivity, within this tradition.

Virginia Held for example states that “Experience is central to feminist thought, but what is meant by experience is not mere empirical observation, as so much of the history of modern philosophy and as analytic philosophy tend to construe it. Feminist experience is what art and literature as well as science deal with. It is the lived experience of feeling as well as thinking, of performing actions as well as receiving impressions, and of being aware of our connections with other persons as well as of our own sensations.” (2006)

Whom would you consider to be your most important teacher(s) and collaborators?

My interest in how care can be embedded in art evolved from considering its perceptual and psychological component since my early studies in Italy, which led to include specific strategies for enhancing social awareness and engagement. This was inspired by artists from the 60s and 70s, whose approaches impact society to this day in different ways. These are, including: the psychology informed approaches by Bruce Nauman, and Grazia Varisco (Varisco taught me at Brera Academy in Milan); the sociology related one by Dan Graham; the active participation and empathy in Lydia Clark’s, and the social actions and positioning by Artists Placement Group (APG) and Steven Willats.

In addition, I partially owe my unconventional research journey to experimental film maker and great mind Malcolm Le Grice, who was the director of studies of my PhD at Central Saint Martins in London from 1998. Generally, in my projects, my collaborators are carefully chosen and approached to take part in the initial investigation and research and/or in aspects of the creative process as participants.

What publications do you consider the most important with regard to care ethics?

I can mention the references which are useful for me to consider a very small portion of this wide area of study, and specifically to do with care in relation to women’s position in society, dialogic strategies and ecology. I would mention Nel Noddings’ developed idea of care as a feminine ethic, drawing conceptually from a maternal perspective (Caring: A Feminine Approach To Ethics And Moral Education, Berkeley: University Of California Press, 1986), and understanding caring relationships to be basic to human existence and consciousness. Also, Annette Baier underscores trust, as a basic relation between particular persons, and as the fundamental concept of morality (Trust and Anti-trust, Ethics 96: 231-60, 1986).

Virginia Held wrote numerous publications on care ethics, in which she construes care as the most basic moral value, and describes feminist ethics as committed to actual experience, and lived methodologies. One of the most recent books is Ethics of Care, Personal Political and Global (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006). Held argues that rights based moral theories presume a background of social connection, and that care ethics can help to create communities that promote healthy social relations. In this context, I argue that art can be a powerful dialogic tool.

Which of your own books/articles/projects should we learn from?

My artistic approach has developed through steps of a personal journey, each of which investigates different aspects of the same unsettled condition of a human being in search for home. However, in the body of work since 2014 the subject matter has become more specific and so has my awareness of the impact of my participatory strategies.

For example, the project Lo scarto, a workshop based project also including 40 sculptures for hand and drawings, developed in Sicily, where Danilo Dolci worked, a process of visualization of the role of listening in dialogue (Unesco and European Funding, 2015), allowed for a non-verbal dialogic strategy to emerge therein. This is discussed in the book chapter Cologni, E. (2016) ‘A Dialogic Approach For The Artist As An Interface In An Intercultural Society’. In Burnard, Mackinlay, Powell, The Routledge International Handbook of Intercultural Arts Research New York, London: ROUTLEDGE.

While the site responsive art project Lived Dialectics, Movement and Rest at Museums Quartier in Vienna, was informed by walks (sic) and research on place attachment in dialogue with US based environmental psychologist David Seamon (discussed at the Leonardo Laser series of talks at Central Saint Martins College University of the Arts London and Westminster University, in 2016, and the Leonardo 50th Conference, 2017, Bologna, Italy, published as Cologni, E. (2018) ‘LOCATING ONESELF’, in The New and History – art*science 2017/Leonardo 50 Proceedings. Capucci and Cipolletta (Eds), Noema Media and Publishing – ISBN 978-88-909189-7-1). This project informed the development of Seeds of Attachment, which, together with my ongoing relevant research will be included in a book.

What are important issues for care ethics in the future?

My interest is now in a possible link between ecofeminism and care ethics (Held) through practices of care. I am trying to embed the adoption of dialogic (inherently interdisciplinary) strategies in the creation of the work, a form of socially engage art practice. These include responding to the spatial (Linda McDowell), social (Henry Lefebvre), and cultural dimension of a place, as well as engaging with specific communities and collaborators therein to create situated (Donna Haraway) and embodied knowledge (Luce Irigaray). My projects often develop through collaborating, and thus becoming part, of interdisciplinary contexts.

For example, the current project was developed in collaboration with the College 250 Archive Working Group and involved subjects like science, education and architecture. However, in my practice, consistent concerns with ecofeminism and place are informed by ongoing conversations with Professor Susan Buckingham (feminist geographer, Cambridge, UK), whereas the artistic strategies with curator Gabi Scardi (Milan, Italy, International Development Fund British Council/Arts Council England, 2018/19), and in reference to historical artists like Mierle Laderman Ukeles (Maintenance Art Works 1969–1980).

How may care ethics contribute to society as a whole, do you think?

I am interested in the fact that it takes us to look at things from a different angle, consider our actions and experience, to then realize how we can contribute to society. More specifically sharing through art, strategies and concerns I have as a mother myself was quite natural, and this will hopefully lead to make people more aware of how they can contribute themselves to society in the everyday. Joan Tronto and Berenice Fisher have defined ‘‘taking care of’’ as an activity that includes ‘‘everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible” (1990), and this is so relevant now and must be implemented at a social and environmental levels.

Do you know of any research-based projects in local communities, institutions or on national levels, where ‘care’ is central?

I have been in touch with different contexts relevant to my art work and research in the UK and beyond, including conducting ongoing dialogue with Ecofeminist Laura Cima (Italy, see my A-N Bursary blog 2018), and the Moleskine Foundation, whose social and pedagogic work through art takes place internationally including Africa. I am always interested in gathering more information about associations and organisations specifically in the context of artistic practice and care, and these include for example: the research centres CAMeO, at the University of Leicester (UK), or the projects Laboratory for Aesthetics and Ecology (Denmark), and Pier Projects (UK).

However, there are many wonderful socially engaged projects, institutions, artists and curators I have been following out there, whose remit is to impact society, and whose approach resonates with care ethics, even if in a wider sense, in terms of supporting social cohesion, denouncing and acting on climate change, address geopolitical issues, support inclusive gender policies, and intercultural dialogue. These are, including: VISIBLE Project (Belgium/Italy), Museum MIMA (UK), Arte Útil by artist Tania Bruguera, curatorial platforms PUBLICS (Finland), Arts Catalyst (UK), Vessel, and Connecting Cultures (Italy), to mention just a few.

Images

- Maud Cloudesley Brereton, The Mother’s Companion (1909), detail from Contents page. Published when Brereton was a mother of five children. She had been honoured by the French Academy for her work in promoting public health. Sir Lauder Brunton, a leading medical practitioner with an international reputation, and a founder of the National League for Physical Education contributed a Preface. Published by Mills and Boon, best known for their popular literature and practical handbooks.

- Display of selected items from the College archive on Maud Brereton and Leah Manning.

- Indoor Gymnastics (1944/5). Photograph of scenes from Homerton’s past, showing students participating in gymnastics classes. Learning about health and moving the body was an important part of historical curricula.

- Installation view in the Ibberson Gymnasium, Homerton College, University of Cambridge. The arrangement of the display was inspired by archival photographs of the room, whose architectural design was punctuated by wooden panels corresponding to the areas in between the curved windows. On view are reproductions of the original items kept in the College Archive, as well as selected sport equipment. The newly produced rope sculptures refer back to the time when the space was used as a gym since it was built in 1914.

- Relations of Care, Elena Cologni (2018, pair of mobile sculptures, steel rods, jute ropes, 2.5 x 2.5 x 2 metres each).

- Care Proximities, Elena Cologni, installation view in front of the Ibberson Building, Homerton College, University of Cambridge (2018, installation including two sculptures and drawing on college lawn: wood + lawn marking paint, 20x100x0.5 meters)

- Care Proximities, Elena Cologni, installation view in the college lawn.

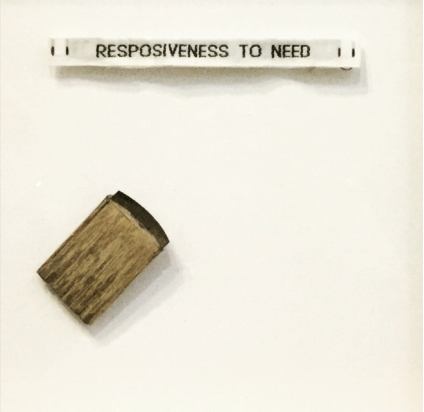

- Installation view including: Mother’s Tools, Elena Cologni (2018, 1 in a composition of 4: wood, steel, custom-made fabric labels, printing tools from the artist’s mother’s embroidery kit, 20cmx20cm each); and Care Notes, Elena Cologni (2018, graphite prints, graphite pencil, laser print on paper, Moleskine Japanese album, with inserts of fabric designs from the Architectural Review Magazine, June 1936, 21cm x 120 cm).

- Mother’s Tools, detail from installation

- Portion of display with content from the College archive, including contents of a needlework box (1861-2). Bought for 12s 6d, this box belonged to Emma Hunter, a student at Homerton College in the early 1860s. Dressmaking was an important skill for students in their adult lives, and in preparing a younger generation of girls at school for home-making and motherhood.

- Care Is Relational, and Care Instructions, Elena Cologni (2018, 2 from series of woven labels, the first of which is inspired by Virginia Held’s writings, and the latter by Maud Brereton’s revolutionary position at the time, that domestic labour should be paid)

Copyright Ó Elena Cologni, Homerton College, University of Cambridge and Moleskine Foundation

Selected References

- Cologni, E. (2016) Dialogic Approach For The Artist As An Interface In An Intercultural Society. In Burnard, Mackinlay, Powell, The Routledge International Handbook of Intercultural Arts Research New York, London: Routledge.

- Cologni, E. (2018) Locating oneself, in The New and History – art*science 2017/Leonardo 50 Proceedings. Capucci and Copolletta (Eds), Noema Media and Publishing (ISBN 978-88-909189-7-1)

- Held, V. (2006) Justice and Care: Essential Readings in Feminist Ethics Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 101-115.

- Held, V. (1993) Feminist Morality: Transforming Culture, Society, and Politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Held, V. (2006) Ethics of Care, Personal Political and Global. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Held, V. (2018) Care Ethics and the Social Contract, unpublished lecture, Oxford.

- Noddings, N. (1982) Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education. Berkeley: University of CA Press.

- Fisher, B. and Joan C. Tronto (1990). Toward a Feminist Theory of Care. In Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives, edited by Emily K. Abel and Margaret K. Nelson. State University of New York Press.

- Tronto, J. (1994) Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. New York, NY: Routledge.

Acknowledgements

The discussed project ‘CARE: from periphery to centre‘ was developed with contributions from University College London Library; Cambridge University Library; The Harlow Art Trust: Gibberd Gallery, Harlow. The project was part of Cambridge Festival of Ideas 2018, was commissioned by Homerton College of the University of Cambridge for the 250th Anniversary Celebrations, and kindly supported by the Moleskine Foundation.

www.elenacologni.com

Copyright Elena Cologni, Homerton College, University of Cambridge and Moleskine Foundation

Text: Ayla van der Boor

Call for papers: Asymmetrical Ethics

Toward an Asymmetrical Ethics: Power, Relations, and the Diversity of Subjectivities

International conference organised November 13 to 15 by the Centre for Studies in Practical Knowledge at the School of Culture and Education, Södertörn University.

Intersubjective relations

In Western societies and philosophical traditions, the egalitarian relation between rational subjects has since long been understood as an ethical ideal for intersubjective relations. This ethics presupposes a relation between two independent subjects of the same kind: autonomous, rational, and (self-)transparent subjects. And even when this understanding of subjectivity is not applicable, the ideal remains the same.

When this egalitarian ethic is applied to, for example, relations between children and adults, humans and animals, care-giver and patients with dementia, teachers and pupils, there is a risk that the variety of subjectivities involved in these relations will not be acknowledged, and thus opens up for a hidden abuse of power. These problems are also relevant for empirical research where asymmetrical relations are at the center, for example research that aims at giving voice to other subjectivities, which also turns this into it a question of methodology and research ethics.

Asymmetrical relations

But are not all relations asymmetrical? Human life itself begins as an asymmetrical relation between a pregnant mother and her fetus. And perhaps, as is the case in this relation, asymmetrical relations need not be based in injustice. We can even ask ourselves if anyone in fact lives up to the ideal of rational subjectivity presupposed by egalitarian ethics. Instead, a description of asymmetries might reach an intrinsic dimension of intersubjective life and an understanding of such asymmetries that would make our understanding of different kinds of subjectivities and relations richer.

But how are we to formulate an ethics of asymmetry that moves away from the long-standing influence of “symmetrical ethics,” which permeates contemporary life? Where, and how, is it needed? How would it be possible to develop an asymmetrical ethics that is not caught up in power abuse, static and rigid relations, or locked in fixed hierarchies? And how can we formulate

an ethics of asymmetry in which the meaning of equality, integrity, power, freedom, etc., can be thought anew?

Questions and topics

We invite researchers from all human and social sciences, as well as artistic researchers and artistic practitioners, to investigate these questions further. Questions and topics may include philosophical issues of asymmetrical ethics, for example the asymmetrical nature of life, asymmetry and power, and asymmetrical relations within an egalitarian ideal. We also invite submissions from broader research areas that may include human-animal studies, disability studies, studies on elderly care, educational relations, childhood studies, theory and methodology of science, etc.

We invite individual papers or panels. Please submit your abstract of maximum 300 words for papers and 600 words for panels to maria.prockl@sh.se, latest August 30, 2019.